Written by Sid Lambert (@sid_lambert)

Talk to any veteran of the early Nineties and the pain of The Bond Scheme, Oldham’s plastic pitch, and watching Mike Small continually flagged offside is still etched in their memories. After the drawn-out demise of John Lyall’s Boys of ’86 ended in relegation, the club was rebuilding slowly with the likes of Slater, Dicks and Morley. They were the flickering lights of hope on a bleak horizon in East London.

David Speedie’s name appears as little more than a footnote of that era. He made just 11 appearances in claret and blue, yet his contribution was vital to re-establishing West Ham United as a top-flight side.

By spring 1993, Billy Bonds had brought some pride back to the Boleyn after the madness of Lou Macari. Whilst the world was watching Sky’s “Whole New Ball Game”, the second-tier promotion race was a sprint to the finish between three teams: Kevin Keegan’s resurgent Newcastle, Jim Smith’s Portsmouth and West Ham.

Keegan’s Toon were free-scoring juggernauts, leaving the Irons and Pompey to battle for the second automatic spot.

Bonds had built an efficient and entertaining outfit. A strong back four was protected by the energy of Peter Butler in midfield, whilst Mark Robson and Kevin Keen offered guile from the flanks. Initially, Clive Allen and Trevor Morley had formed a tidy partnership up front. However, injury to Allen meant that West Ham spent the second-half of the season solely reliant on Morley for goals.

After a tame 1-0 loss to Notts County, there was an expectation that Bonds might dip into the loan market. Though few were impressed when he actually did.

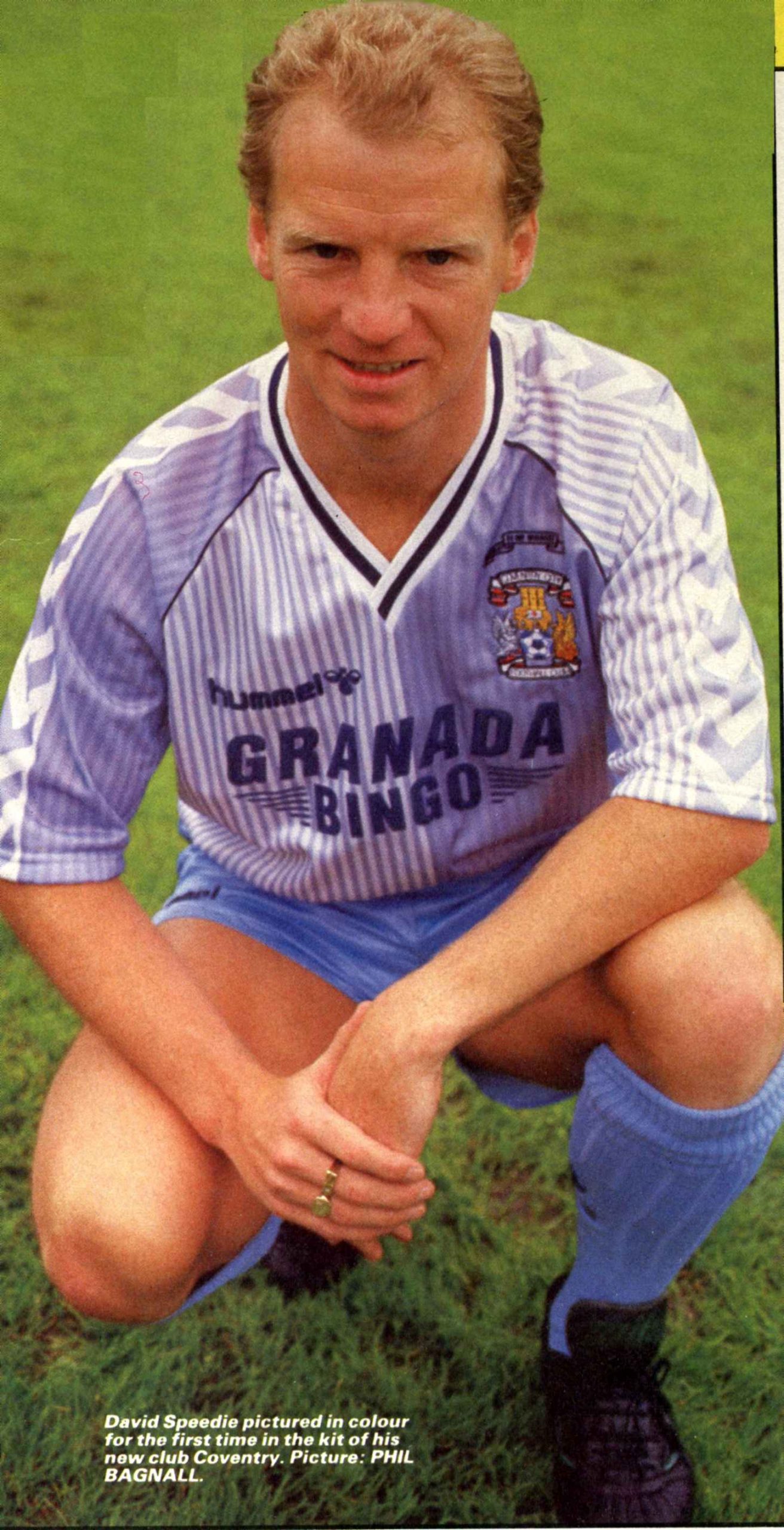

David Speedie was a former Scotland international who’d made his name partnering Kerry Dixon at Chelsea in the mid-Eighties. He then had a success at Coventry before a surprising move to Kenny Dalglish’s Liverpool in the twilight of his career.

The son of a coalminer, Speedie was a hard-nosed character who didn’t shrink from confrontation. He’d called Graeme Souness a “muppet” during his Scotland debut and then told Sir Alex Ferguson to “stick it” when offered a standby role for the World Cup squad in 1986. Speedie considered himself an automatic choice.

His playing style was equally abrasive. Despite being just 5’7” he would go toe-to-toe with the biggest and toughest centre-halves around. He’d scrap for every ball. Chase every lost cause. Long before gegenpressing became fashionable, he was making a nuisance of himself both physically and verbally. Loathed by opposition fans, he was adored by his own. Yes, he was an arsehole. But he was a very effective arsehole.

By March 1993, Speedie had become a loan ranger. His time at Liverpool was cut short when Souness arrived at Anfield as manager, and a successful spell at Blackburn had ended when Southampton insisted he was part of the deal that took Alan Shearer to Ewood Park. The move to the south coast was a disaster. Speedie was shunted out to Birmingham and West Brom, doing little to impress at both.

There was nothing to suggest that he was the man to boost West Ham’s promotion prospects. Bonds thought otherwise. Having crossed paths with the firebrand striker throughout the previous decade, he knew that Speedie had that little bit of bastard about him that his current squad was lacking. He also had a knack of scoring in important games, a habit that would come in handy during the final throes of an epic season.

The early signs weren’t good. Though his industry was never in doubt, Speedie looked rustier than Robert Maxwell’s wristwatch in front of goal. When he missed a late sitter in a 2-2 draw with Millwall, there were murmurs of discontent from the terraces. After five goalless appearances, that included two defeats, the dissent was growing louder.

The pressure was on when Leicester City came to Upton Park in front of the ITV cameras. It was exactly the sort of occasion that Speedie had relished over the years. Once again, he delivered. Two instinctive finishes eased the tension as Bonds’ side coasted to a 3-0 win. Speedie could have had four, but with the pressure off he spurned two glorious chances late in the game. It was almost as if it was too easy.

He scored again on another nervy afternoon to help secure a 2-1 win over Bristol Rovers and West Ham went into the final game of the season – at home to Cambridge United – clinging onto that precious second spot. Portsmouth had self-destructed the previous week, losing 4-1 at Sunderland and letting Billy Bonds’ side sneak ahead on goals scored.

The gaffer knew that a win alone might not be enough. Pompey had a banker at home to Grimsby. The Irons faced Cambridge, who needed a result to rescue themselves from relegation. After a 46-game slog, the race to the Premier League was going down to the wire.

There’s been a lot written about Upton Park’s demise in recent times. It may not hold the same gravitas as Manchester United on the Boleyn’s swansong, but that afternoon against Cambridge on May 8, 1993 was up there with the greatest of days on Green Street.

The ground was packed to the proverbial rafters. The stands reeked of sweat and Silk Cut. And in-between the nervous inhalations and occasional bursts of ‘Bubbles’, you could hear the buzz of transistor radios as punters waited for news from Portsmouth.

Steve Potts received his well-deserved Hammer of the Year trophy before the game and that was the only highlight of the first half as both sides struggled with nerves. News filtered through that Portsmouth were bottling it too. Bonds settled his men down and sent them out for a crucial second half.

It took only two minutes for Speedie to make his mark. Julian Dicks won a header from a corner and the loan striker spun his marker to smash home off the underside of the bar. It was his fourth goal in his eleventh – and final – appearance and he’d set West Ham on the way to the Promised Land.

Substitute Clive Allen scored the tap-in that confirmed promotion. The ball had barely crossed the line before the pitch was besieged by an almighty horde of pitch invaders. By that time, Speedie was sat on the bench, having been substituted minutes earlier. When you watch the celebrations from that day, you remember the images of Billy Bonds pumping his fists in joy and Clive Allen drenched in champagne. You forget David Speedie appearing as an awkward also-ran, toasting West Ham’s future knowing he was unlikely to play any part in it.

It was a historic day. West Ham were back in the big time. And David Speedie’s contribution should never be forgotten.

About the author: Sid Lambert (@sid_lambert) is a football writer who recently published his new book Cashing In. It tells the story of Ray Cash, a 19-year-old footballer making his way through the murky world of the Premier League back in 1990s, when football changed forever. You can buy it here.